Intro: “Indian exports growth to the US slowed to 7.1% compared to over 20% in the preceding four months, as U.S. tariffs hit, shaking textiles. Despite this, August trade gap narrows at $26.49 bln vs July's $27.35 bln as gold import ease and oil prices soften at $69. Banks look cleaner, yet risks rise in personal loans. DFIs like NaBFID must fund infra, where both risk and tenor exceed banks abilities – to avoid past mistakes. Diversifying exports to ASEAN & Africa, and cutting logistics costs are urgent. Reserves cover 75 days—energy security and competitiveness hinge on reforms ahead,” asserts Economist and Researcher Divya Srinivasan. She dissects the recent issues that plague the Indian economy. Take a read at the exclusive interview with Mahima Sharma of Indiastat only on Socio-economic Voices.

MS: You’re seeing a sudden 50% U.S. tariff on many Indian goods - quantify the potential direct hit to the U.S.-bound Indian exports and name the hardest-hit sectors. Also explain two of these sectors with examples, putting light on why these will be the highest hit, highlighting how the entire supply chain is affected.

DS: India exported USD 86.5 bn of goods to the US in FY25, nearly one-fifth of total exports. Of this, close to USD 47 billion is directly vulnerable to the higher tariff, excluding sectors that are exempt or already face sector-specific duties. There has already been some front-loading, between April-July FY26, exports to the US increased by 21% y-o-y (to USD 33.5bn) as firms rushed shipments ahead of the tariff hike. But with tariffs in effect from August, the drag will intensify. Under conservative assumptions, if just half of the vulnerable basket is lost, India’s exports to the U.S. could still take a hit of USD 12-15 bn, even after accounting for frontloading.

Many of the labor-intensive sectors are hardest-hit by the 50% tariff such as textiles and apparel, gems & jewellery, leather and footwear, and fisheries. Together, these rely on the U.S. for 30-50% of their exports, over 80% in the case of fisheries, placing millions of jobs in both formal and informal segments at risk.

Consider textiles and apparel, where the U.S. is the single largest market. Made-up textiles are especially vulnerable: 48% of India’s exports go to the U.S., while the next-largest markets (UAE, UK) account for barely 5% each. With Asian peers like Vietnam and Indonesia facing lower tariffs and offering similar products, the impact is harder. It is the second largest employment generating sector (after agriculture), employing over 45 million workers.In the case of fisheries, over 80% of our exports are in the US and puts fish farmers at risk.

If the 50% tariffs remain in place, other countries like Ecuador, Vietnam etc. could expand capacity and capture market share. However, in gems & jewellery too, the U.S. is the single-largest market. But then the alternative destinations such as the UAE and the EU already absorb a sizable share. This offered some cushion against the shock.

MS: With US deliberations on tariffs against Indian exports in mid-2025 - what trade and domestic reforms should India prioritise to protect exporters, diversify markets and secure resilient value-chain participation?

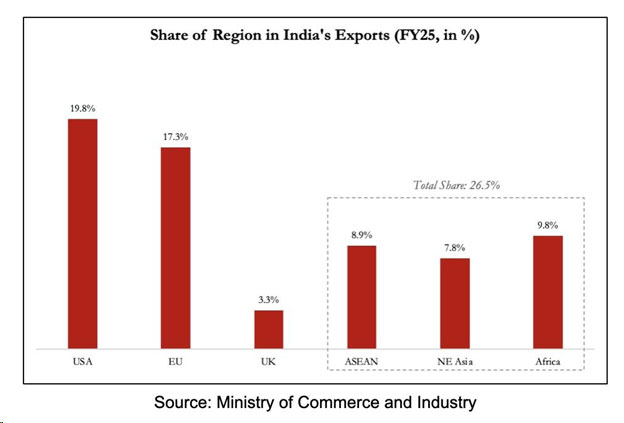

DS: The US and EU together account for over a third of India’s exports (19.8% and 17.3% respectively in 2025). The UK added another 3.3%. By contrast, regions that are expected to drive future global export growth - ASEAN (8.9%), North-East Asia (7.8%), and Africa (9.8%). But these remain under-tapped. India should deepen engagement with its neighbors in Asia and build stronger commercial ties with Africa. The latter is a rapidly growing consumer market. At the same time, negotiating with the US remains critical, given that many of our labor intensive sectors rely on American demand.

The government is contemplating measures to safeguard exporters, in the textile sector they have provided import duty exemption on cotton till the year end to help lower input cost. Recent rationalisation of GST slabs is a step forward, but faster refunds and resolution of unutilised input credits are needed. Equally important is strengthening trade finance access for MSMEs, which are most exposed to tariff shocks. Loan moratoria and emergency credit lines could provide cushion in the short term with support to industries to access new markets.

In the longer term, India needs to strengthen multiple levers of competitiveness.

MS: India’s merchandise exports fell to US$35.14 billion in June 2025 while overall exports were US$67.98 billion. What are the underlying sectoral weaknesses or external shocks driving this divergence? How can India preserve trade competitiveness amidst global tariff threats and slowing advanced-economy demand?

DS: Merchandise exports in June 2025 were marginally lower (-0.1%) than a year ago. But then, the composition reveals the underlying drivers. Oil exports contracted by nearly 16%, reflecting softer crude prices: India’s oil basket averaged USD 69.8/bbl (vs USD 82.6/bbl last June). In contrast, non-oil exports grew by 2.9%, supported by engineering goods, electronics, chemicals and readymade garments. Exports to the U.S. also rose, helped by front-loading ahead of the tariff hikes.

To preserve trade competitiveness amidst global tariff threats and slowing advanced-economy demand, India needs a three-pronged strategy (as highlighted earlier): Regional diversification, global value chain integration and reducing domestic bottlenecks.

MS: Brent crude averaged US$69 per barrel during June–July 2025. How do such sustained price levels affect India’s current account, inflation and fiscal balances? What medium-term energy security and hedging strategies should policymakers consider under such conditions?

DS: Brent crude averaging around US$69 per barrel in June–July 2025, well below last year’s levels of over US$80. India being a net importer of oil (petroleum products account for more than a quarter of India’s imports), this provides meaningful relief.

On the current account, owing to softer oil prices net oil imports (imports minus exports) fell to 3.2% of GDP in Q1 FY26 from 3.3% in Q1 FY25, helping cushion the current account deficit.

On inflation, the impact is visible in recent data. Wholesale inflation was negative in both June and July. This eased out the input cost. With enough global supply, oil prices are expected to remain manageable this year. This would be helping keep inflationary pressures contained.

Energy security remains a big challenge because India imports over 80% of its oil requirements. India currently maintains strategic petroleum reserves (SPRs) at three sites (Mangalore, Padur, and Vizag). These can store up to 5.33 million tonnes of crude. These reserves, along with storage held by oil marketing companies, cover about 75 days of fuel demand. Plans are underway to expand this capacity to cover 90 days. This would be creating a stronger safeguard against supply disruptions or price spikes.

MS: India’s trade deficit narrowed – August trade deficit at $26.49 bln vs July's $27.35 bln Which structural vulnerabilities and cyclical import surges contributed most to this imbalance? What external sector adjustments can be envisaged without destabilising growth momentum or currency stability?

DS: See, the merchandise imports contracted by 10.1% while exports rose 6.7%. Exports growth to the US slowed to 7.1% compared to over 20% in the preceding fourth months. On the import side, a sharp fall in gold inflows (down 57% from last August due to higher prices and a high base) helped narrow the trade deficit.

Looking ahead, external sector adjustment must come. These should be from structural shifts rather than one-off measures:

Such steps can narrow external imbalances over time while preserving growth momentum.

MS: By March 2025, gross NPAs of public sector banks dropped to 2.58%. Does this headline decline reflect genuine balance-sheet repair or transitory resolution effects and what's the path ahead?

DS: This fall has touched the lowest in over a decade. This decline does reflect meaningful balance-sheet repair.

Banks have cleaned up legacy stress through stricter recognition norms, better provisioning, and government recapitalisation, while corporates have significantly deleveraged since the last credit cycle.

Importantly, the composition of bank lending has also shifted. Post-2015-16, the share of credit to industry has declined (from 38% in Mar-16 to 22% in Mar-25), while retail lending has risen (19% to 33% in the same period). As I have documented in my work, the last NPA cycle was heavily driven by exposure to commodity-sensitive sectors and large infrastructure loans. That concentration has reduced, limiting systemic vulnerability. The IBC has also been a structural reform, providing banks with a framework for resolution, even if outcomes have been slower than initially envisaged. DFIs are coming back into the picture to handle sector-specific lending roles.

The challenge now is to preserve these gains. Risks are rising from rapid growth in unsecured personal loans, global tariff shocks affecting exporters. Sustaining low NPAs will require stronger governance, sharper early-warning systems, and a deeper role for capital markets so banks aren’t again overburdened with long-term project risk.

MS: With NaBFID scaling up disbursements in mid-2025, how can expanded DFI lending crowd in private investment while avoiding fiscal risks? What governance safeguards are essential to prevent hidden contingent liabilities from destabilising public finances?

DS: With NaBFID scaling up there is an opportunity to recalibrate and improve the financing mix for infrastructure.

In our recent research paper with my co-authors, we show that India’s last major infrastructure push in the 2000s leaned too heavily on commercial banks (as DFIs wound down and corporate bond markets were shallow). Banks were pressed into funding long-term, risky projects that they were never designed to handle. The result was a surge of NPAs that weakened bank balance sheets. Ultimately the government stepped in with costly recapitalisations.

Infrastructure remains central to India’s developmental needs and goals and the government has rightly prioritised it in recent years. Since last year, disbursements by NaBFID have picked up, with half of these going to longer-term infra projects. Alongside providing long-term financing, NaBFID must also bring in project expertise, technology and analytics. Together these can improve preparation and risk assessment and monitoring.

MS: Imports rose in July 2025 after softening in June. How should India’s trade policy navigate between import substitution and global integration amid such fluctuations?

DS: Recent movements in imports have been driven by commodity prices, majorly oil and gold, rather than structural shifts. With prices of gold surging this year, gold imports have dropped. Our core imports have been growing year to date.

In broader perspective, India can do a lot in terms of rationalising tariffs. Although our average tariff rates have reduced from 30% in the late 1990s to around 6% now, they are still substantially higher than our Asian neighbours (1.3%, 1.7% and 2.4% in Vietnam, the Philippines, and China, respectively). Participating in GVCs becomes difficult with such tariff differences and import restrictions. High tariffs on imports are effectively equivalent to taxes on exports, making us less competitive in global markets.

MS: India increased crude imports from the US in August 2025. How does this shift reshape India’s energy trade diversification, geopolitical exposure and trade balance? What vulnerabilities does it create for refining economics and strategic reserves?

DS: While I have not seen hard data yet, it is likely that crude imports from the US rose as prices became competitive. The government has been clear in terms of its energy purchase stance. The government is ready to head in the direction that best serves India’s interests.

On the energy security front, as mentioned earlier, the government is already planning to expand strategic petroleum reserves. India has also increasingly improved its energy mix by expanding renewables capacity. Additionally, the government is promoting use of natural gas and alternative fuels such as ethanol, biofuels, compressed biogas and green hydrogen.

MS: With SCBs reporting improved asset quality mid-2025, what framework of provisioning, monitoring and stress-testing is required to ensure sustainable lending discipline in infrastructure loans with long gestation and high default risks?

DS: We need to develop stronger channels for financing infrastructure and not overly rely on banks.

Scheduled commercial banks (SCBs) have reported improved asset quality. Sustaining this requires a framework that avoids a repeat of past cycles, especially in infrastructure or related sectors.

Provisioning needs to be forward-looking and counter-cyclical with continuous monitoring that is closely linked to project milestones.

That said, the larger shift should be institutional. Banks are not designed to shoulder long-term infrastructure risk. That role is best played by DFIs like NaBFID, which can provide patient capital, sector expertise, and absorb early-stage risks.

Reference Links

About Divya Srinivasan

Divya Srinivasan is an economist with a leading private sector financial institution. She holds a Master’s in Economics from the Delhi School of Economics. Her interests lie at the intersection of macroeconomics, finance and policy. Her current work focuses on understanding the slowdown in the Indian economy during the 2010s, as well as themes of financial stability and long-term growth. She has presented her research at prominent national and international economic conferences, engaging with leading scholars and policymakers. Her commentaries on the Indian economy are regularly published in national dailies.

About the Interviewer

Mahima Sharma is an Independent Senior Journalist based in Delhi NCR with a career spanning TV, Print, and Online Journalism since 2005. She has played key roles at several media houses including roles at CNN-News18, ANI, Voice of India, and Hindustan Times.

Founder & Editor of The Think Pot, she is also a recipient of the REX Karmaveer Chakra (Gold & Silver) by iCONGO in association with the United Nations. Since March 2022, she has served as an Entrepreneurship Education Mentor at Women Will, a Google-backed program in collaboration with SHEROES. Mahima can be reached at media@indiastat.com

Disclaimer : The facts & statistics, the work profile details of the protagonist and the opinions appearing in the answers do not reflect the views of Indiastat or the Journalist. Indiastat or the Journalist do not hold any responsibility or liability for the same.

"AI, GCCs and Green Investment will reshape India's Future Growth"... Read more